The Orthodox Christian philosopher David Bentley Hart wrote that his liking for anarcho-monarchism as political philosophy comes from his “exactingly close readings of The Compleat Angler and The Wind in the Willows.”

The Orthodox Christian philosopher David Bentley Hart wrote that his liking for anarcho-monarchism as political philosophy comes from his “exactingly close readings of The Compleat Angler and The Wind in the Willows.”

To which I would add the new documentary Our Nixon. But more on that later.

By anarcho-monarchism, Hart meant the odd combination of anarchism and unconstitutional monarchism advanced by the fantasy writer and Oxford medievalist J.R.R Tolkien. Tolkien’s ambiguously governed Shire and his character Aragorn’s alter egos as Ranger Strider and Returning King in The Lord of the Rings reflected their creator’s penchant for anarcho-monarchism on Middle-earth, his fantasy overlay of our Earth. But not coincidentally, his book helped inspire many a young environmentalist including your unworthy blogger. Elsewhere I have traced the source of the appeal of Tolkien’s fantasy writing to a range of people with environmental concerns, from eco-anarchists in England to religious conservatives and counter-culturalists in America. Other book-length studies have detailed the environmental meaning of Tolkien’s work.

The riddling portmanteau term “anarcho-monarchism,” as exegesized by Hart, symbolizes aspects of the biblical notion of dominion related to the ecosemiotic idea of pansemiotic cosmology, important to the twenty-first century environmental imagination. Hart writes that ,

“There are those whose political visions hover tantalizingly near on the horizon, like inviting mirages, and who are as likely as not to get the whole caravan killed by trying to lead it off to one or another of those nonexistent oases. And then there are those whose political dreams are only cooling clouds, easing the journey with the meager shade of a gently ironic critique, but always hanging high up in the air, forever out of reach… the only purpose of such a philosophy is to avert disappointment and prevent idolatry. Democracy is not an intrinsic good, after all; if it were, democratic institutions could not have produced the Nazis. Rather, a functioning democracy comes only as the late issue of a decently morally competent and stable culture. In such a culture, one can be grateful of the liberties one enjoys, and use one’s franchise to advance the work of trustworthier politicians (and perhaps there are more of those than I have granted to this point), and pursue the discrete moral causes in which one believes. But it is good also to imagine other, better, quite impossible worlds, so that one will be less inclined to mistake the process for the proper end of political life, or to become frantically consumed by what should be only a small part of life, or to fail to see the limits and defects of our systems of government. After all, one of the most crucial freedoms, upon which all other freedoms ultimately depend, is freedom from illusion.”

The key here is an iconographic experience of imaginative politics, rather than an idolatrous or objectifying politics–thus to “be less inclined to mistake the process for the proper end of political life, or to become frantically consumed by what should be only a small part of life, or to fail to see the limits and defects of our systems of government… [to practice] freedom from illusion.” I have written in the introduction to my new collection, Re-Imagining Nature: Environmental Humanities and Ecosemiotics, on the relation between the visual theory and practice of Byzantine iconography and Charles Peirce‘s triadic model of sign relation. Rather than the binarized Saussurean capture of signified and signifier within an arbitrary interiority of human self, Peirce’s model (influenced, I argue, both by apophatic Christian theology and by Native American thinking) suggests how our self is formed symbolically in our environmental, cosmic, and spiritual relationships. Such simultaneously personal and cosmic symbolism, interacting reciprocally with both the real and the imaginary, rather than subject to them, melds what we have come to divide as the analogic and digital aspects of life, the wave and the particles, so to speak.

“This universe is perfused with signs,” Peirce wrote, exemplifying pansemiotism, a model of the cosmos as all-meaningful and life itself as informationally symbolic. It is found in many pre-modern or non-modern worldviews as well.

Peirce’s pansemiotism lends itself to an apophatic sense of cosmic hierarchy, as an organismic mystery of networks of energy, originally described in writings attributed to St. Dionysius the Areopagite. This differs from the model of hierarchy commonly found in the modern West, that of a static organizational order.

The pre-modern apophatic but pansemiotic sense of hierarchy as mystery, as a cosmic organism that is not organizational, but which involves energies of unknowable essence, can be found in foundational texts of English poetic tradition such as the opening and structure of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, and the Mutabilitie Cantos’ end to Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. This dynamic sense of hierarchy is found, too, in Hart’s short list of readings on anarcho-monarchism, both of which not coincidentally relate directly to ecology.

The Compleat Angler and The Wind in the Willows are both classic celebrations of the English rural countryside as a meaningful landscape of symbolism, more than Virgilian pastoralism in which the landscape as celebrated tableau becomes a surrogate of the state. By contrast, the flow of nature symbolism in both books is more anarchistic and humble, yet within a framework of an overall order.

An opening verse to Izaak Walton’s and Robert Cotton’s The Compleat Angler (which appeared in final form in 1676) states “The world the river is; both you and I , and all mankind, are either fish or fry.” The book as a whole emphasizes the contemplative worth of fishing, and explores the meaning of “angling” in poetry by Dryden and others as well as explanations of the art. What emerges is a sense of the relationship of Angler, river, and fish, and the combined spiritual and practical aspect of the activity. The book identifies Anglers with the fishers of the gospels. In a section on angling law, it calls for community spirit and expects riverfront landholders to be hospitable to anglers on the water who may also be trespassers “upon so innocent an occasion.”

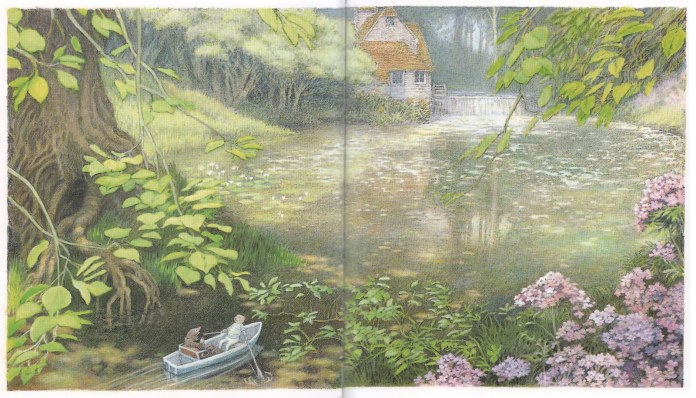

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame evokes a similar emphasis on hospitable camaraderie amid a shared natural world, an appreciation for friendship in helping Toad regain his manorial home after an invasion by gangster weasels from the Wild Woods, but also the importance of the egotistical toff Toad learning humility from his still affectionate friends. The meaningfulness of nature is also celebrated in this animal fable. As Rat puts it, “There is nothing–absolute nothing–half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” Mole encounters the river, “as one, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spell-bound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.”

The Christmas caroling of young field mice celebrating the Nativity of Christ and the mysterious appearance of the demigod Pan to Mole and Rat while searching for a lost baby otter (Pan, called Friend and Helper, also seeming to be, despite his horns, a type of Christ of sorts in that animal realm), all shape a Peircian sense of embodied cosmic meaning or pansemiotics.

Which gets us back to Hart’s anarcho-monarchism. Of course he was jesting at least in part when referencing these two decidedly non-political books as the source of his political philosophy, as a kind of combined manifesto for imaginary anarcho-monarchism, seen also in Tolkien’s liminal Rangers of the North and South in The Lord of the Rings, and in the rather blurry governmental status of the Shire as a province of some missing kingdom. To Christians of these latter days, amid the “great forgetting” about which Rod Dreher writes, such an ambiguous situation is the norm, with no real Christian kingdoms left in the world, and Orthodox Christians left only with allegiance to the vanished empire of Byzantium.

Yet in a time of global neocolonialism and diaspora, real and virtual, allegiance to an imaginary empire is not such a bad thing, especially if this involves an iconographic rather than idolatrous sense of politics. This motivates us in our home to fly a Byzantine flag between our neighbors’ competing American flags, which are on one side of us traditional red-white-and-blue and the other a rainbow-version of Old Glory, calculatedly representing a local political binary. Perhaps this spring we’ll add a plaque next to our front door reading “Byzantine Consulate,” to further confuse that binary. But will such imaginary diplomatic immunity shield our household, patriotic American citizens all, from unwanted attention from the NSA or other agencies of our government, along our quiet bank of the Susquehanna River?

Still, in the absence of a kingdom of higher meaning, we engage the meaningfulness of Nature in our own circles of organic community, as we hope for and have faith in the return of the King of the cosmos, for news that Aslan is on the move. And in resistance to global technocracy devoted either to bureaucratic or capitalistic meaninglessness, what remains for Orthodox Christians whose empires have long since disappeared are the “little kingdom” of the family and the “little church” of the parish and home, the crowned king and queen of the Orthodox Christian marriage ceremony, the royal priesthood of the Church’s laity, the little conciliar monarchies also of monastic communities and bishoprics in the Church. And in society at large are the “little platoons” of Edmund Burke’s organic society resisting both totalizing ideology and materialism, amid the inherent royalty of all human beings as sons of Adam and daughters of Eve in the image and likeness of God, despite all of our objectifying fallen state as human beings. All this diversity in unity in society reflects, for Orthodox Christians, the mystery of the Trinity, the apophatic sense of the essence of God, the symbolic conciliarity of the Trinity as best we can understand it, seen in St. Andrei Rublev’s famous icon, and the idea advanced by Fr. Sergei Bulgakov of society as a household, an oikos, as in the Greek root of both economy and ecology, overlapping.

In our larger secular society, America’s Declaration of Independence provides a pansemiotic lead-in to the U.S. Constitution by referencing “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” The Constitution itself, as James Fenimore Cooper noted in his classic The American Democrat, draws on elements of what were seen as the “natural” three forms of human government drawing on Classical models, monarchy (the presidency), aristocracy (the Senate), and democracy (the House of Representatives). In its federal system and system of checks and balances, it drew on Iroquois notions of government. It also parallels in a certain secular sense the ideas of conciliarity, symphonia, κοινωνία, and sobornost in ancient Eastern Christian tradition. But all those organic aspects of the Constitution only become highlighted when related to the pansemiotic aspects of imagination, of iconography in a sense, rather than idolatry, as mentioned above. The third foundational document of American politics, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (the 150th anniversary of which our family shared at Gettysburg, PA, recently) offers an added gloss on the pansemiotism of true government, including a reference to the nation (rather than an end in itself) being “under God.”

Lincoln’s message as a whole underlines a point made recently by Tadodaho Sid Hill, spiritual leader of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. Tadodaho Hill noted to a group of visitors including myself at the Onondaga Longhouse, which is the headquarters of the Confederacy, that the U.S. had erred in its “separation of church and state” by making a merely mechanical borrowing of Iroquois approaches to politics, which mechanical or legalistic approach to government lies at the heart of our environmental crises. From the point of view of Hill’s Native anarcho-monarchism, or Hart’s Orthodox Christian anarcho-monarchism, the endorsement of liberal democracy by another Orthodox scholar, Prof. Aristotle Papanikolaou, must always be a highly qualified one.

The challenge is to avoid idolatry of today’s technocratic system, in which, as the cultural theorist Slavoj Žižek has noted rightly (despite his own problematic consumerist-psychoanalytic Marxism) global capitalism and identity politics alike become mere extensions of Stalinism.

Which gets me around to the documentary Our Nixon as an addendum to Hart’s list of books as a source for an iconographic rather than an idolatrous political philosophy.

Recently I introduced the documentary and led a discussion of it afterward at the Campus Theatre in downtown Lewisburg, PA.

The documentary evoked for me the memory of long-ago family arguments, involving mainly now-silent voices, about Nixon, a great but flawed president in very turbulent times, who not incidentally achieved much on environmental issues, despite his disastrous fall. Director Penny Lane and colleagues used an impressionistic but empathetic lens for the film, focused through the home videos of three young clean-cut Nixon aides, two of whom were members of the Christian Science Church, in which some of my extended family were members, and to which I belonged when I was younger. In many ways Nixon wielded symbolic leadership through media with skill, despite personal awkwardness, but his insecurities and over-reaching, writ large as a result, helped spur the unraveling both of his administration and the symbolic mystique of the presidency and the Constitution.

Chuck Colson, a Nixon aide who went to jail for his misdeeds and then left politics to organize a prison ministry, commented on the spiritual hollowness at the heart of the U.S. imperial presidency, which he witnessed in the time of the president to whom he was so devoted, the distantly Quaker Nixon. Indeed, the Disneyesque devotion to the American status quo of Nixon’s staff, however admirable the unifying aspects of his leadership in a chaotic time, merely raised a false idol for many. The resulting disappointment highlighted the problem raised by Hart, of political idolatry rather than iconography, looking for either materialistic or idealistic saviors in political figures or systems in a post-Christian world. Despite all the travails and supposed lessons of Watergate and Nixon’s disgrace, as I also noted at the Campus Theatre, more systematic government spying and abuse of power abound.

Returning home from the movie theater, I picked up both The Compleat Angler and The Wind in the Willows to read a few favorite passages before bed, thinking of Hart’s essay, Nixon’s fall, and mounting crises today that face us in terms of finding meaningful life amid a faltering economy, expanding technocracy, and roiled natural environment.

Voltaire’s Candide urged us to cultivate our gardens. But as Tartu semiotician Timo Maran affirms, cultivating a garden in an ecosemiotic sense is no withdrawal from community life–no more, in an infinitely deeper way to an Orthodox Christian, than is hesychastic prayer, whether in urban or wilderness deserts. Rather, tending one’s ecosemiotic garden can be a deeper way of re-working and re-imagining the transfigurative symbolism that constitutes life in community, in the household cosmology that really is ecology, an iconography of nature memorably book-marked by Hart under “anarcho-monarchism.”

“Put not your trust in princes,” we hear the badly flawed but Holy Prophet King David sing, recognizing the king and queen in all of us with all our many limitations, tending community and meaning, as we await the return of the King.

Portrait of Vice President Nixon in 1960 by Norman Rockwell. President Obama poses for a selfie with the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain and the Social Democrat Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt of Denmark at the memorial service for Nelson Mandela in South Africa.

Portrait of Vice President Nixon in 1960 by Norman Rockwell. President Obama poses for a selfie with the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain and the Social Democrat Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt of Denmark at the memorial service for Nelson Mandela in South Africa.